Why This Response by APS Matters to Aviation Safety and Saving Lives

Over 30,000 pilots annually participate in APS-certified Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) at US and international airlines, government agencies, US militaries, corporate flight departments, and flight schools. Now in our third decade of providing UPRT at our multiple US and European locations, APS has a crystal clear picture of how and why UPRT improves the knowledge, skills, resiliency, and discipline of pilots while increasing safety throughout fixed-wing aviation. Our purpose is We Help Pilots Bring Everyone Home Safely and is central to the APS Vision.

In the article “Why Upset Training Just Doesn’t Work,” published by Air Facts Journal, the author attributes airplane upsets to ‘careless’ or ‘poorly trained’ pilots and shares several opinions as to why upset training will not prevent Loss of Control In-flight (LOC-I) related accidents. Unfortunately, these representations display a general lack of understanding of modern Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) while perpetuating an outdated view of what today’s UPRT accomplishes. A clarification of some basic facts about UPRT and LOC-I prevention would establish a foundation from which a more robust and insightful discussion can be presented.

With that said, there are a number of points made by the author we agree with:

- The primary objective of effective upset training is to prevent an upset from happening in the first place,

- Operational airplanes typically have different spin characteristics than the airplanes used in upset training, and

- Upset training improves stick and rudder skills, and probably makes pilots more cautious and precise.

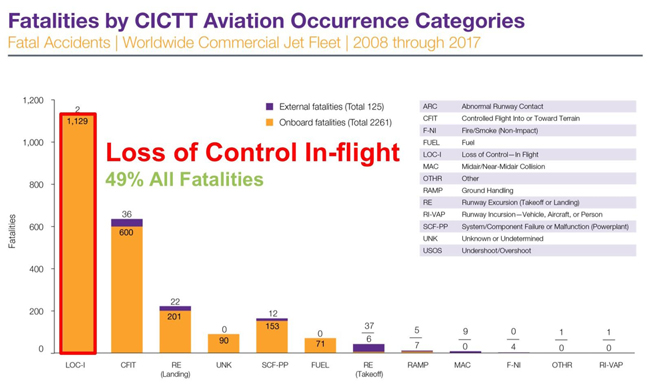

Assessment of the LOC-I Threat in Relation to Pilot Competence

As the author has observed, discussions on the subject of UPRT are increasing. This is because LOC-I is the leading cause of fatalities in every sector of aviation according to the NTSB and a diversity of other informed entities to include the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the FAA, and the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST). For commercial airlines worldwide, for example, according to CAST in the excerpt from the Boeing report below, LOC-I now accounts for over 49% of all fatalities. This relative contribution has increased in severity to an all-time high over the last seven years of this report.

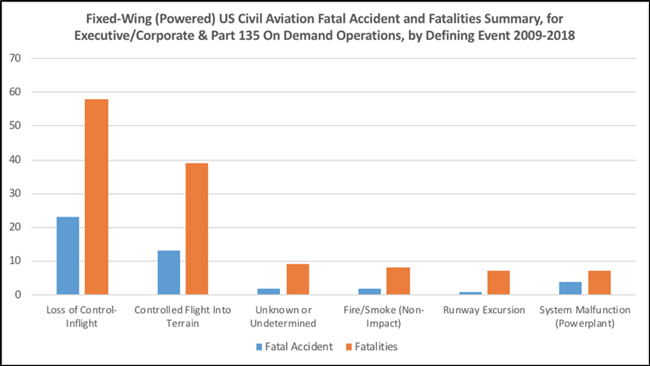

Most would agree that these are hardly ‘careless’ and ‘poorly trained’ pilots. Let’s bring it closer to home and look at recent NTSB findings over the last 10 years between 2009 and 2018, narrowed down to the professional pilot sectors of aviation in the United States. These sectors include Part 135 on demand and executive/corporate flight operations that tend to follow training regimes similar to the airlines.

LOC-I tops both the number of fatalities and the number of fatal accidents. LOC-I prevails as the #1 threat even to the ‘best of the best’ pilots immersed in professional flight operations. Sadly, the situation is far worse when we look into non-professional aviation statistics. Enough said on mistakenly attributing LOC-I to careless and untrained pilots. Let’s move on to the solution.

Solutions to LOC-I as Published in the Air Facts Journal Article

What the article proposes to do to address this tragic and unnecessary loss of life is to essentially continue the same training that has led us to the problem as it exists today. Training that has established LOC-I as the #1 fatal threat to aviation safety industry-wide. The author does not seem aware that industry leaders, safety experts, and regulatory agencies are not only talking more about upset training, but they are also implementing regulatory mandates for the very training being dismissed by the article. But, why?

Real-world Survivors Thanks to UPRT

The reason is that these safety experts and industry leaders have taken a hard look at the problem and the evidence that UPRT presents a safe, effective solution, and after years of study and consideration of actual real-life evidence, their expert opinions were that upset training DOES work. We have experienced the same. Here are just a few stories from pilots who have completed a comprehensive UPRT program to use their skills to recover their aircraft and likely save their lives and the lives of their passengers:

- Dave Newland – Global/Challenger pilot with over 17,000 hours

- US Army Pilot – Surviving an Ice-induced Airplane Upset

- Michael Smith-Wheelock – Traffic Pattern Event

Because taking solution-oriented steps to reduce the risk of LOC-I is of such great importance, it’s essential to address the numerous misconceptions presented by the Air Facts Journal individually. The high-level topics that encompass these misconceptions are summarized as follows:

14 Issues with ‘Why Upset Training Just Doesn’t Work’

- Recovery Empowers Prevention

- Regulatory and Industry Acceptance of UPRT

- Aerobatics are not UPRT

- Spin Prevention is Key

- Instrument Recoveries in UPRT

- It’s Not About Fun

- Transfer of Skill

- Simulator Limitations in UPRT

- Human Factors and Air France 447

- Technological “Silver Bullets”

- Airplanes vs. Simulators for UPRT

- Wake Vortex Encounters

- UPRT Instructor Qualification

- The False Premise of Existing Flight Training

1. Recovery Empowers Prevention

The article itself provides more than ample evidence for exactly why Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) is required to improve aviation safety. We can all agree, for example, that we should strive to prevent an upset before it begins. What we differ on is the best way to do this. In the author’s telling, it is to continue more of the same training we do today — that is, maintain the same status quo that has propelled LOC-I to the top of the list as the most fatal threat in aviation. In his question, “Wouldn’t it be much more valuable than upset training to train and practice our basic instrument flying skills?”, the author seemingly accepts the premise that our existing pilot training system is not missing a thing, and we just need to do it better. Perhaps a better question is, What if there is a better way to improve the prevention of LOC-I? Or, What if there is a way to dramatically reduce the threat of LOC-I while simultaneously improving pilots’ everyday airmanship, manual flight operations proficiency, and decision making?

If we provide pilots with knowledge and skills that are not currently required as a part of existing licensing training, yet critical to their survival when faced with an airplane upset, it expands their available “toolkit”. A pilot undertaking modern, comprehensive UPRT confronts a variety of developing upset events in order to master the safest and most efficient way to recover. The author asserts that “to experience an upset, a pilot must first lose control of the airplane.” That is incorrect. An upset is the beginning of an escalating path that may end in a LOC-I. While the skills required at the onset of an upset may exceed skills required by typical licensing training, UPRT expands a pilot’s capabilities to enhance their capacity to respond promptly and correctly to such events while they are still in control and able to influence the outcome, thereby preventing an LOC-I event. The fundamental focus of UPRT is impeding a developing upset event at the earliest stage possible along the escalating pathway of an upset event that could lead to a loss of control.

“This structured training builds an enhanced mental model for the pilot; one that develops and improves a pilot’s pattern recognition of an escalating upset event.“

What takes place in UPRT as pilots learn correct recovery techniques is a variety of controlled entries into upsets so they can repetitively practice and ingrain effective intervention strategies from virtually any recoverable flight condition. As a result of this process, pilots witness various escalating pathways that lead to airplane upsets. This structured training builds an enhanced mental model for the pilot; one that develops and improves a pilot’s pattern recognition of an escalating upset event. The process of UPRT improves pilots’ ability to intervene earlier in the onset of an undesired aircraft state, hopefully before it gets to the point of a developed upset event that requires recovery.

This demonstrated boost to prevention strategies is why the FAA, EASA, ICAO and other regulatory and safety organizations do not call this training Upset Training anymore as the author has in his title. The correct terminology is “Upset Prevention and Recovery Training” because this training has evolved monumentally beyond the authors understanding of UPRT implementation.

2. Regulatory and Industry Acceptance of UPRT

After studying the problem for nearly a year and receiving testimony from experts throughout the world, the FAA’s Loss of Control Avoidance and Recovery Training Aviation Rulemaking Committee concluded with recommendations for implementing improvements to existing training practices by integrating a comprehensive upset prevention and recovery training (UPRT) program. One of their chief recommendations was to provide UPRT-specific training in actual flight at the commercial pilot licensing level on light airplanes which are capable of performing the recommended maneuvers while maintaining acceptable margins of safety.

ICAO accepted and adopted this recommendation, and changed their own recommendations for Commercial Pilot licensing worldwide to include it. While yet to be acted on by the United States, EASA began requiring 3 hours of on-aircraft UPRT along with 5 hours of academics in December of 2019 and the 11 countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations begin a similar requirement in 2020.

3. Aerobatics are Not UPRT

The author makes the statement that “with an aerobatic instructor, the trainee rolls and tumbles through extreme attitudes” and that “what you learn tumbling through the sky in an upset recovery course won’t do any good in real life flying in a business jet, or even a personal piston single.” If proper UPRT involved as much tumbling as the author asserts, and if any aerobatic instructor could be a competent UPRT instructor, then he might have a point. However, neither is a valid description of proper UPRT. Unfortunately, these particular statements, more than any of the misunderstandings presented, reveal the stark lack of expertise and perspective specific to this domain of training which lead to the unfortunate effort to assert and defend the article’s title.

To begin with, the author seems to make the incorrect assumption that aerobatics and UPRT are the same thing simply because they both involve all-attitude/all-envelope flight. That is about where the similarity ends. Aerobatics involves precision flying of prescribed figures to achieve a known outcome. Recovering from upsets involves non-precision maneuvering to safely and effectively respond to an unexpected situation. In many ways, the two types of flying are at the opposite end of the spectrum in regards to the human factors concerned.

Existing guidance from the ICAO Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (Document 10011) states it best, “It is important to make the distinction that UPRT is not synonymous with aerobatic flight training. While aerobatic training does improve manual handling skills and increased awareness of the results of flight path deviations, its primary objective is to achieve proficiency in precision manoeuvring. The primary objective of UPRT is effective aeroplane upset prevention and recovery. From the human factors aspect, aerobatics does not specifically address the element of “startle”. Nor does aerobatic flight training necessarily provide the best medium to develop the full spectrum of analytical reasoning skills required to rapidly and accurately determine the course of recovery action during periods of high stress. UPRT should address these psychological and reasoning responses, which are significant factors in most LOC-I accidents.” (Section 3.3.1.3)

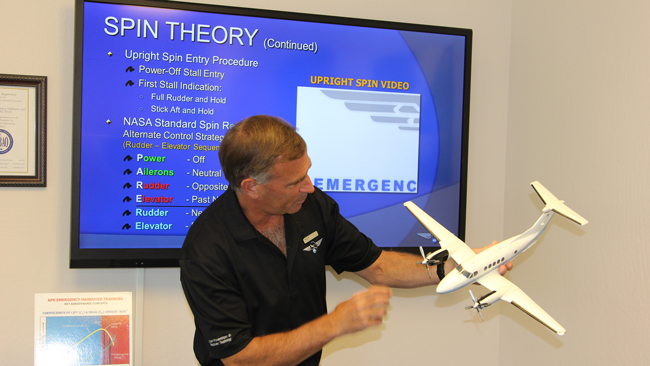

4. Spin Prevention is Key

The author makes the point that operational aircraft will have different spin recovery characteristics than the aircraft used in training. This is generally true, and in fact, as he points out, there is no guarantee that the airplane that pilots fly outside of training will be recoverable at all. That is why in most cases (depending on the certification and recoverability of the student’s normal aircraft) spin recovery is not the most essential point. It is learning and fully understanding how a spin develops and how to effectively stop the developing escalation of events from unintentional slow flight, to approach to stall, to stall, to incipient spin and beyond that can result in an unrecoverable spin. The spin recoverability of the training platform, such as the 1-turn intentional spin certification of normal category airplanes, simply provides a margin of safety for training in the various factors which contribute to a spin. For example, as addressed by APS CEO, Paul BJ Ransbury in his article titled ‘Spinning Normal Category Aircraft – What’s the Risk?’, according to FAA Advisory Circular 61-67C, the 1-turn spin certification is “to provide a margin of safety when recovery from a stall is delayed”. It’s not to intentionally spin normal category airplanes.

Let’s remember that there is no requirement for Commercial or ATP pilots to ever see a spin. Providing pilots with orientation to spin considerations through robust UPRT provides powerful information and deterrent value that immensely assists spin prevention efforts beyond the requirements of typical pilot certification training.

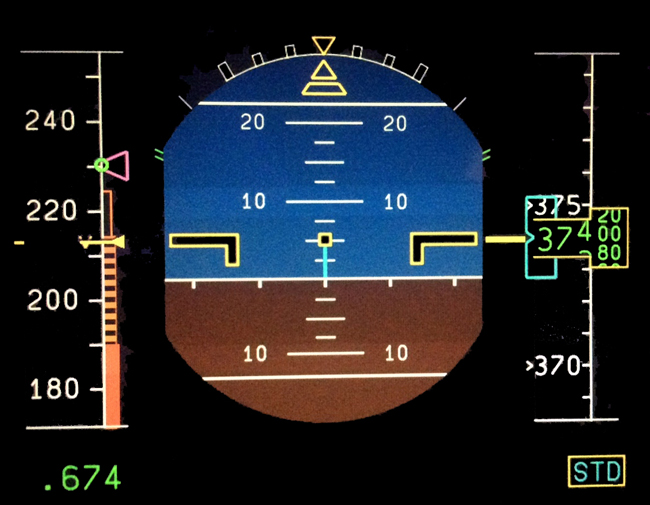

5. Instrument Recoveries in UPRT

Next, let’s take a look at the author’s statement that “flights are always done in visual conditions.” This statement is incorrect. One of the major differences between aerobatics and UPRT is that although aerobatics must be (by regulation) done in VFR conditions, comprehensive UPRT must include recoveries accomplished by instrument references alone. This is easily done using a view limiting device and is essential since we know from the accident record that vulnerability to upset events is much greater when in instrument meteorological conditions or at night.

6. It’s Not About Fun

Before we go further, there is a matter irrelevant to this debate: fun. The fact that some people may enjoy UPRT is often used to dismiss the valuable contribution of UPRT, as in, “they are just doing it because it’s fun”. For some people UPRT is fun, for others it is not. That is not the point. What should be debated is the value of the training in mitigating the LOC-I threat. Nothing is as effective as properly delivered, comprehensive UPRT for that purpose. There is virtually no industry organization or regulatory agency in the world that has not acknowledged the role that UPRT can play in reducing the threat of LOC-I while also improving flight envelope awareness, manual handling proficiency, and enhancing aeronautical decision-making as a result of increased awareness, knowledge, and experience.

7. Transfer of Skill

Now let’s address the author’s point that “an upset recovery course won’t do any good in real life flying in a business jet, or even a personal piston single,” because it is related to the misconception that there is no distinction between aerobatics and UPRT. The key concept here is transferability, and it is the UPRT instructor’s responsibility to convey this at all times. As stated in the ICAO Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training: “The delivery of UPRT in an aeroplane should not be focused on aeroplane-specific performance or features. Appropriate use of aeroplane training platforms for the delivery of UPRT should emphasize the introduction of general principles of understanding and techniques which may be applied to a wide range of aeroplanes and are not in conflict with commercial air transport aeroplane recovery techniques.” (Section 3.3.1.2)

Just because a training aircraft platform is certified to pull significant G’s doesn’t mean that capacity is used in delivering UPRT, it just provides an additional margin of safety. Just because it can roll fast, does not mean that capability must be utilized. Correctly utilized, the all-attitude capable training aircraft is only used as a surrogate for the airplane the pilot in training normally flies. So it is flown in a similar manner, to the same limit load (2.5G for most transport category aircraft) and similar roll rate. This is where a qualified UPRT instructor works as a facilitator to provide only transferable skills that can be used in the student’s own aircraft. Are the control forces different, sure; but the analysis and management of angle of attack, lift vector orientation, energy management, and flight path stabilization are concepts that are driven by the laws of aerodynamics and physics. Techniques can be taught that are transferable to any fixed-wing aircraft. For an expanded discussion on the role and relevance of Transfer of Skill in UPRT, please review the article titled ‘Transferability in Upset Prevention and Recovery Training’ by APS Vice President of Training, Randall Brooks.

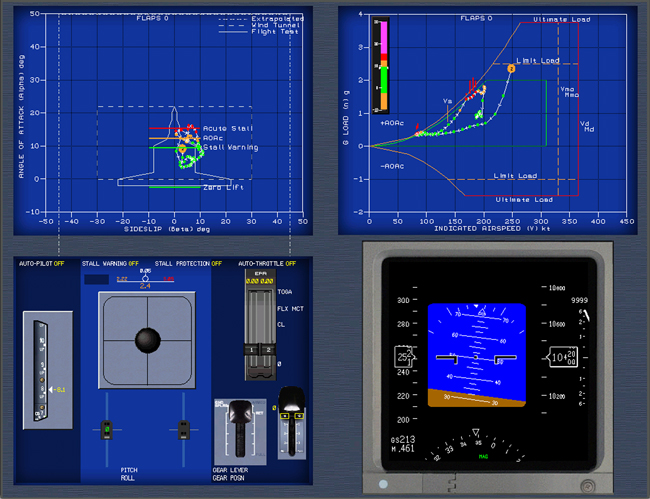

8. Simulator Limitations in UPRT

Another significant misconception is the assessment of what simulators can, and cannot, do when the author suggests that rather than UPRT it would be more effective to have pilots learn to “deal with instrument and equipment failures in high fidelity simulators”.

Let’s be clear, nothing since humans learned to fly has provided a greater contribution to aviation safety and enhanced pilot training more than flight simulation. Flight simulation is highly accurate in the domain where we normally fly, but can be highly invalid in the upset domain, where flight testing for the simulator has not gone in the past. However, flight simulation has two major limitations which render it an incomplete solution when it comes to the mitigation of LOC-I. The first are the aerodynamic limits of aeromodeling, and the second regards human factors response in upset events.

Regarding Air France 447, the author states that the pilots “had all been trained to lower the nose to recover from a stall since their earliest days as student pilots, so it wasn’t more training that was required, upset or otherwise.” This statement fails to recognize several facts that distinguish regular stall training from UPRT, which when understood more clearly indicate why UPRT in actual flight complements simulator training so effectively.

What is often called stall training is generally only approach to stall training, where recovery takes place at the first indication of stall, which is prior to the full aerodynamic stall. UPRT goes beyond the actual stall warning to educate pilots how aircraft behave beyond the stall, which is quite different; it is so different that the FAA has required all airline simulators to support FAR 121.423 Pilot: Extended Envelope Training to be modified to illustrate those differences by extending the modeling past the aerodynamic stall. A few non-airline aircraft simulators have been modified with these extended or enhanced aeromodels, but even then none of them can fully duplicate what aircraft do in the dynamic conditions that can be present in upset events. In fact, FAR 121.423, that addresses stall and upset prevention and recovery training, is in response to a Congressional mandate, Public Law 111-216 Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010, that specifically highlights the critical importance of training being dismissed by the author.

We all want pilots to recover at the first indication of a stall, but history shows us again and again that in real life it does not always work out that way. Why not provide pilots with additional knowledge and training that can equip them to deal with aircraft behavior beyond the stall?

9. Human Factors and Air France 447

In the case of the pilots of Air France 447 it was the unfamiliar behavior of the aircraft beyond the stall that was one of many factors confusing them. Because of the post stall roll instability seen in most aircraft, but not seen in approach to stall training in simulators, none of the pilots fully comprehended their situation. The author asks if the crew could “have maintained control without any airspeed indication if they had been upset trained?” and answers himself, “Probably”. He explains that it would have been more likely “if the confusion and stress hadn’t been so high” and notes that the “cockpit workload would have been so over-the-top”. That is the single greatest contribution of UPRT. Explaining and showing pilots how aircraft will behave in an upset reduces confusion so that stress is not so high. For pilots who have had UPRT the cockpit workload in such events will not be incapacitating. They will be prepared for what is happening to them, and understand how to respond correctly even in confusing, time-critical, life threatening situations.

The author acknowledges human factors, to an extent, when he discusses “an instructor determined to give you more emergencies, failures, and complex approach procedures than you can handle. Overload can and will happen to any of us.” However, this comparison underestimates the intensity of the human factors impact of an unexpected airplane upset. In the simulator, you know you are not in danger and your life is not at risk. What the author is explaining is task saturation, or performance anxiety. That does not begin to approach the kind of cognitive overload, surprise, and startle that can overwhelm pilots in an unanticipated upset event. Simply put, the ‘been there, seen that’ value of UPRT is just the beginning of the development of the resilience, discipline, and cognitive agility in crisis required to both arrest an escalating airplane upset, and recover if necessary.

This gets to the root cause of the LOC-I problem, which the author never addresses, other than a passing admission that UPRT “courses can be eye-opening for a pilot who has never flown beyond a 60 degree bank, or 20 or 30 degrees nose up or down.” The root cause of the persistence of LOC-I as the #1 fatal threat in aviation is: existing pilot licensing training does not prepare pilots adequately for the differences they can encounter aerodynamically, psychologically, and physiologically beyond the normal flight envelope.

10. Technological “Silver Bullets”

In proposing a solution to the fate of Air France 447, and perhaps other potential upset accidents, the author offers that “there is a technical solution that could have saved the day for that Airbus crew over the Atlantic. It’s synthetic airspeed.”

APS is all for technical solutions to the LOC-I problem and embrace those solutions as a part of the experience and tools necessary to overcome LOC-I. After all, LOC-I is not the second or third leading cause of fatalities, it is the number one cause in every sector of aviation around the world. The industry should embrace every proven and effective idea to be found. The problem with technological fixes, or patches, is that they are unreliable. The supposition the author makes is that if the technology didn’t work, what we need is more technology. Let’s not forget that the Air France 447 accident aircraft was equipped with a very advanced technological solution that was supposed to prohibit this exact scenario from being possible–until it happened. Angle of attack limiting through fly-by-wire, flight envelope protection was developed in order to make airplanes like this “unstallable”; yet the airplane stalled. And this is not the only example of an Airbus, presented to the industry as an unstallable airplane, losing control as a result of aerodynamic stall resulting in a fatal crash killing all on board; consider Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501 in 2014.

Regardless of the technology employed, the flight crew always remains the last line of defense for the control of an aircraft’s flight path.

Regardless of the technology employed, the flight crew always remains the last line of defense for the control of an aircraft’s flight path. What needs to be patched is not our technology, but a pilot training system that inadequately prepares pilots for situations such as what the crew of Air France 447 encountered. Providing the flight crew with training that enhances their control of the aircraft if it leaves the normal flight domain, UPRT equips them with a safety net that is available regardless of the degradation of their automation or systems.

11. Airplanes vs. Simulators for UPRT

Understanding the aerodynamic and human factors limitations of flight simulation helps to explain why all-attitude/all-envelope aircraft are required to deliver the full story in UPRT. Flight simulation is useful, and can be very valuable in delivering many aspects of LOC-I awareness and prevention. The author states that he doesn’t think that pilots can be trained to respond reliably and predictably “in the panicked few seconds that follow” an airplane upset. Part of that may be because he believes that a pilot must, as he put it, “respond perfectly”. That is the difference between recovering from upsets and many other flying skills. Upset recovery does not need to be done perfectly to be effective. It just needs to be done in a manner that safely and effectively returns the aircraft to the heart of the normal flight envelope where it belongs. This capability is most thoroughly ingrained by training in the domain where actual aerodynamic and human factors considerations are encountered in an upset: in flight.

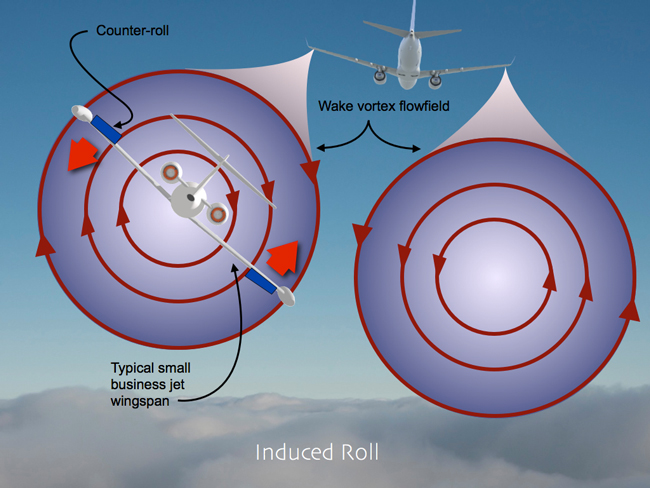

12. Wake Vortex Encounters

The author acknowledges that the threat of a wake vortex encounter “has caused a number of pilots to lose control and crash”, and goes further to describe an event which occurred from an aircraft “well beyond the time and distance parameters that would have normally made its wake a threat.” He then asks the seemingly rhetorical question, “With so little altitude available, is our upset-trained ace going to roll a business jet through a full 180 degrees or more and not lose more than the altitude available?” The answer is yes. There are documented examples of pilots who have used such training to save their aircraft, their lives, and their passengers’ lives. Why haven’t most pilots heard of these “saves”? Because safe outcomes are not generally found in the news, and rarely in accident reports.

13. UPRT Instructor Qualification

One item that’s agreed is that bad UPRT won’t fix a thing. The problem is that in his article the author appears to make the assumption that all UPRT is bad UPRT. Bad training is just bad training, whether it is learning to solo, training in a sophisticated flight simulator, or UPRT. To paint all UPRT with the broad brush of incompetence depicted is inaccurate. Standardized UPRT based on solid research and testing provides results in mitigating the risk of LOC-I. While the industry has not adopted training standards to regulate the safe and effective delivery of UPRT, Aviation Performance Solutions has proposed a path forward for this guidance in the Every Pilot In Control Solution Standard™ (EPIC-S2™).

One critical element of UPRT addressed in the EPIC-S2 is the question — How do we know what a good UPRT instructor is? For a CFI to teach instrument or multi-engine skills, they need a CFI rating particular to that skill that demonstrates they have certified knowledge and skills in that area of instruction. Anyone that has mastered the art of teaching appropriate UPRT knows that there is as much or more knowledge and skill required to correctly teach UPRT than either instrument or multi-engine training. When instructors are required to demonstrate their knowledge and proficiency in delivering UPRT as they are required to for other specialized instructional skill sets, an objective standard can be set and UPRT instructors can be safely trained and qualified.

14. The False Premise of Existing Flight Training

In the article, the author states that upsets happening to well trained and careful pilots who are following all procedures is a false premise. There is no doubt that well trained and careful pilots who are following all procedures minimize their chances of an upset. We can all agree that is an excellent starting point. However, the author certainly knows that not all pilots fit that description. The attitude taken by the article simply seems to be that if pilots get into an upset they deserve their fate. Why should we be opposed to giving pilots a fighting chance even if they make a mistake? Why does the industry wholeheartedly insist on redundancy in our aircraft and its systems (certification calls for it), yet when it comes to pilot training, we do not provide the redundancy, the safety net, that UPRT can provide, whether an upset is a pilot’s fault or not. That’s all changing thanks to ICAO and it’s Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training being adopted worldwide for all the right reasons.

To give clarity to the author’s point, the most significant false premise presented is that our current pilot training system cannot be improved upon in order to reduce the harrowing LOC-I accident rate. Along with the vast majority of industry stakeholders, APS witnesses on a daily basis that the rate can be reduced, and that the comprehensive integration of UPRT is the most efficient and effective means.

The persistent misconception shared by many, may best be understood through Hans Christian Andersen’s story, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. In the story, it takes the clear eye of a child to see that the Emperor’s clothes were not fine; they were missing. And so it is with our current training, the Fine Training the author and others want us to stick with is not so fine after all. It is missing the elements that can effectively help pilots prevent and recover from upset events.

Flight training is completely adequate in the normal envelope, where most pilots fly all the time. However, if pilots are unfortunate enough to leave the normal envelope, whether it is due to their own fault or not, evidence proves that our present system is inadequate to prepare them for what they might face, and what they might need to do differently in order to recover. In those cases, the Emperor’s fine flight training is not so fine at all. Like the Emperor’s New Clothes, it is nonexistent in explaining how aerodynamics and human factors are different from where they normally fly, and what they must do differently to survive.

AVIATION’S MARCH TOWARD SAFETY

Contrary to the personal opinions shared by the author, UPRT is consistently supported by aviation industry organizations. In-flight UPRT is now recommended by ICAO prior to Commercial licensing, is currently required by EASA, and will be required later in 2020 by ten countries in Asia. It is recommended by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) for airlines, is required for all ATP pilots as part of the ATP Certification Training Program, and for all airline pilots in the US beginning in 2020.

The history of aviation has been a shining example for the world in how to mitigate threats and improve safety through change. It is a shame that some cannot accept that it is only through change that we can reduce the threat of LOC-I, and that change has a name. It is called Upset Prevention and Recovery Training.

At the conclusion of his article, the author concedes that “An upset training course can certainly make any of us more precise pilots, and probably more cautious pilots. Enhancing stick and rudder skills is always a good thing” and asserts that “avoiding the loss of control is what matters in every case.” APS generally agrees with both sentiments although they lie in stark contrast to the vast majority of the positions taken throughout the entire article prior to the author’s conclusion.

“Pilots that need UPRT the most, are convinced they don’t”

There is one recurring theme that echoes across APS’s three decades of firsthand experience delivering UPRT solutions to airlines, government agencies, corporate flight departments, insurance agencies, and flight schools; that confounding theme is simply this: Other than a rare and highly-specialized segment of the pilot population with careers immersed in the all-attitude, all-envelope operational flying environment, “Pilots that need UPRT the most, are convinced they don’t”.

In closing, effectively and comprehensively implemented modern Upset Prevention and Recovery Training has the potential to be the single most significant improvement in aviation safety since the advent of flight simulation. Bad UPRT is at best a waste of time; at it’s worse it can be the source of devastatingly fatal LOC-I accidents as evidenced by American 587 in 2001 out of New York. Let’s choose to do it right.

We Help Pilots Bring Everyone Home Safely

Further Reading

Comments: