Effects of G-Forces

Your APS UPRT training will emphasize the flight envelope (i.e. limit load or G-limit) of the aircraft you typically fly. Depending upon your specific aircraft, the range of g-loading targeted for your training at APS will vary from between 2.5 G to 3.8 G. In some cases, utility and aerobatic category pilots may be requested to implement recoveries utilizing up to 4.4 G and 6.0 G respectively. To be clear: we will not be going out and pulling 8 G’s just because we can. This serves no practical purpose and is of no value whatsoever in being competent in emergency maneuver training.

Positive-G

If an aircraft is accelerated in the pitching plane by increasing the angle of attack of the wings, it will move in a curved path and be subject to increased loading. This increased loading is measured in factors of “G” and is felt by the pilot as an apparent increase in weight. In straight-and-level flight a pilot experiences 1G but when he/she moves the stick back to enter a climb, loop, or banks the aircraft into a level steep turn, the pilot will experience a force greater than 1G. For example, in a 60-degree bank turn at a constant altitude, the pilot will experience 2G’s and feel twice as heavy (G-factor, or load factor, of 2). If a pilot pulls 4G’s in a maneuver, he will feel four times heavier (G-factor of 4).

High positive G has the following effects:

- The blood becomes ‘heavier’ and tends to drain from the head and eyes to the abdomen and lower parts of the body.

- The heart is displaced downwards by its ‘increased weight,’ thus increasing the distance it has to pump the ‘heavier’ blood to the brain and eyes.

- Greater muscular effort is required to raise the limbs and hold the head upright.

As a result of (1) and (2), the eyes and brain could become starved for oxygen resulting in ‘grey-out’ followed quickly by ‘black-out’, and then, if the g-loading is sustained, g-induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC).

Your instructor will give you special training on how to combat these forces and show you how to work effectively in this environment. Awareness is the key to G-force management. Blackout and loss of consciousness are extremely rare and will be actively avoided during your flight training. Your instructor has thousands of hours of training in the high-G environment and will always be in the aircraft to ensure your complete safety.

Grey-out is blurred vision under positive g-load accelerations; blackout is a dulling of the senses and seemingly blackish loss of vision under sustained positive g-load accelerations; loss of consciousness is characterized by a total lack of awareness or physical capability and can take up to several tens of seconds to regain sufficient awareness to effectively recover after the g-load situation is returned normal.

Due to the latent period before the symptoms of g-affects occur, it is possible to tolerate high ‘G’ for short periods. Illness, hunger, fatigue, lack of oxygen and the common ‘hang-over’ decreases tolerance. Tolerance varies with individuals, but the average pilot will black-out between 3.5 and 6G’s after five seconds, ‘graying-out’ at about 1G less, and losing consciousness at about 1G over. During periods of grey-out or blackout, normal vision will return as soon as the high G-forces are reduced.

Important Note: Tests have shown that under rapid G-increases of 1G/sec or greater, or when applying positive-G immediately after a maneuver involving negative-G, a pilot may lose consciousness without experiencing blackout, and that recovery may take up to thirty seconds. A lot can happen in that time. This is called the “Push – Pull Effect” and your instructor will be monitoring the flight to ensure that rapid G-onset is minimized. Smooth, positive control of the aircraft is the key reducing exposure to the “push-pull effect”.

To help reduce the effects of positive-G, the “Anti-G Straining Maneuver” should be practiced and used whenever you are under g-loading above normal levels. It involves tightening the legs and abdominal muscles and ‘bearing down’ which is accomplished by trying to exhale but not allowing air to escape. This creates extra tension on the abdominal muscles and constricts the veins and arteries to minimize the amount of blood that pools in the lower body. The pilot should inhale … wait three seconds … exhale approximately 20% of lung capacity over a 1 second interval and then immediately inhale to repeat the sequence. The muscle contraction of the extremities and abdomen should be sustained throughout the G exposure.

Negative-G

When the pilot feels the G-forces acting in the reverse direction to normal (as in sustained inverted flight, an outside loop or an inverted spin), this is known as negative-G. Excess blood is forced into the head and ‘red-out’ occurs at about –4G to –5G. Unlike positive G’s, there is no known straining maneuver that can be accomplished to counter the effects of negative G. You will be spending very little time in negative G flight. It is not the purpose of this training to teach you how to fly at negative G (or even zero G).

Spatial Disorientation

The body uses three integrated sensory systems working together to determine orientation and movement in space. First, the eye is by far the largest source of information. Second, the Somatosensory System refers to the sensation of position, movement, and tension perceived through the nerves, muscles, and tendons. This is the “Seat of the pants” part of our flying. The third sensory system is the Vestibular System which is a very sensitive motion sensing system located in the inner ears. It reports head position, orientation, and movement in three-dimensional space.

During your training, getting back to the basics of flying the attitude and envelope of the aircraft will be of primary importance. Using your eyes to avoid extreme flight conditions and, if encountered, using them to regain control is also an important skill that must be learned and practiced. Statistically, ninety percent of the Loss of Control In Flight (LOC-I) accidents happen in visual meteorological conditions (VMC). It’s no accident that much of your training will be in VMC. Flying can sometimes cause your three sensory systems to supply conflicting information to the brain, which can lead to disorientation. During flight in VMC, the eyes are the major orientation source and usually prevail over false sensations from other sensory systems. When these visual cues are taken away, as they are in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), false sensations can cause a pilot to quickly become disoriented.

Your training will focus on teaching you where to look, scan, and focus your eyes through the varied phases of flight in VMC. Those of you staying for the Instrument Recovery Training (IRT) will learn how to use your instruments in IMC for recognition, avoidance and recovery from extreme flight attitudes.

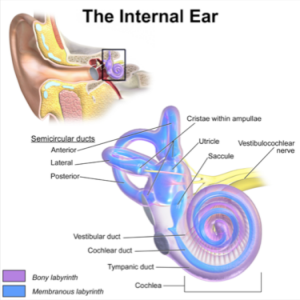

The vestibular system’s primary purpose is to enhance vision. The second purpose, in the absence of vision, is to provide perception of position and motion. On the ground, the vestibular system provides reasonably accurate perception of position and motion. In flight, however, the vestibular system may not provide accurate assessment of orientation. In both the left and right inner ear, three semicircular canals are positioned at approximate right angles to each other. Each canal is filled with fluid and has a section full of fine hairs. Acceleration of the inner ear in any direction causes the tiny hairs to deflect, which in turn stimulates nerve impulses, sending messages to the brain. The vestibular nerve transmits the impulses from the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals (Figure 2) to the brain to interpret motion.

The vestibular system’s primary purpose is to enhance vision. The second purpose, in the absence of vision, is to provide perception of position and motion. On the ground, the vestibular system provides reasonably accurate perception of position and motion. In flight, however, the vestibular system may not provide accurate assessment of orientation. In both the left and right inner ear, three semicircular canals are positioned at approximate right angles to each other. Each canal is filled with fluid and has a section full of fine hairs. Acceleration of the inner ear in any direction causes the tiny hairs to deflect, which in turn stimulates nerve impulses, sending messages to the brain. The vestibular nerve transmits the impulses from the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals (Figure 2) to the brain to interpret motion.

Your training will concentrate on learning “when” and “if” to trust your vestibular system in order to detect an unsafe safe flight condition and affect a safe recovery, if needed.

The somatosensory system sends signals from the skin, joints, and muscles to the brain that are interpreted in relation to the earth’s gravitational pull. These signals determine posture. Inputs from each movement update the body’s position to the brain on a constant basis. “Seat-of-the-pants” flying is largely dependent upon these signals. The body cannot distinguish between acceleration forces due to gravity and those resulting from maneuvering the aircraft, which can lead to sensory illusions and false impressions of the airplane’s orientation and movement.

As we know, some early pilots believed they could determine which way was up or down by analyzing which portions of their bodies were subject to the greatest amount of pressure. We now understand that the seat-of-the-pants “sense” is completely unreliable as an attitude indicator. However, when used in conjunction with visual references, “seat of the pants”, is critically important as we learn how to use it effectively to determine angle of attack and g-loading- but not flight attitude. This will be clearly explained during the course of your training and you will apply this knowledge in several practical situations.

Causes of Spatial Disorientation

There are a number of conditions and factors that will increase the potential for SD. Some of these are physiological in nature (human factors) while others are external factors related to the environment in which the pilot must fly. Awareness by the pilot is required to reduce the risks associated with these factors.

Personal Factors

Mental stress, fatigue, hypoxia, various medicines, G-stress, temperature stresses, and emotional problems can reduce a pilot’s ability to resist SD. A pilot who is proficient at accomplishing and prioritizing tasks with an efficient visual and instrument crosscheck and is mentally alert as well as physically and emotionally qualified to fly, will have significantly less difficulty maintaining orientation.

Workload

A pilot’s proficiency is decreased when he/she is busy manipulating cockpit controls, anxious, mentally stressed, or fatigued. This leads to increased susceptibility to SD.

Inexperience

Inexperienced pilots are particularly susceptible to SD. A pilot who must still search for switches, knobs, and controls in the cockpit has less time to concentrate on visual references and instruments and may be distracted during a critical phase of flight. It is essential for an effective crosscheck to be developed early and established for all phases of flight to help reduce susceptibility to SD.

As we all know, every pilot is susceptible to SD. One would hope that the difference between an inexperienced pilot and experienced pilot is that the experienced pilot would recognize SD sooner and immediately establish priorities to reduce its affects. Denying the existence of SD by inexperienced pilots has been a major contributing factor to countless LOC-I accidents.

Proficiency

Total flying time does not protect an experienced pilot from SD. More important is current proficiency and the amount of flying time in the last 30 days. Aircraft mishaps due to SD generally involve a pilot who has had limited flying experience in the past one month period. Vulnerability to SD is high for the first few flights following a significant break in flying.

Instrument Time

Pilots with less instrument time are more susceptible to SD than more instrument experienced pilots.

Phases of Flight

Although distraction, channelized attention, and task saturation are not the same as SD, they contribute to it by keeping the pilot from maintaining an effective visual or instrument crosscheck. SD incidents have occurred in all phases of flight, in all kinds of weather but are particularly prevalent during the takeoff and landing phases of flight. Aircraft acceleration, speed, trim requirements, rates of climb or descent, and rates of turns are all undergoing frequent changes. The pilot flying on instruments may pass into and out of VMC and IMC. At night, ground lights can add to the confusion. Radio channel changes and transponder changes may be directed during critical phases of flight close to the ground. Unexpected changes in climb out or approach clearances may increase workload and interrupt an efficient crosscheck. An unexpected requirement to make a missed approach or a circling approach at night in IMC at a strange field is particularly demanding. All of these factors and more can significantly increase the potential for SD.

Prevention of SD Mishaps

- Recognize the Problem. If a pilot begins to feel disoriented, the key is to recognize the problem early and take immediate corrective actions before aircraft control is compromised.

- Reestablish Visual Dominance. The pilot must reestablish accurate visual dominance. To do this, either look outside if visual references are adequate or keep the head in the cockpit, defer all nonessential cockpit chores and concentrate solely on flying basic instruments.

- Resolve Sensory Conflict. If action is not taken early, the pilot may not be able to resolve sensory conflict.

- Transfer Aircraft Control. If the pilot experiences SD to a degree that interferes with maintaining aircraft control, then consider relinquishing control to a second crewmember (if qualified) or, if available and capable, consideration should be given to using the autopilot to control the aircraft if the flight attitude is not severe.

Minimizing Motion Sickness

During your training at APS, it’s possible for the student to experience motion sickness. Besides being uncomfortable, it limits your ability to learn. At APS we have tailored our courses in consideration of the fact that some students will experience some form of motion sickness during the course. Syllabus rides are organized so that all objectives can be easily accomplished within the five-ride program, even with an average occurrence of motion sickness.

Causes of Motion Sickness

Apart from physical disorientation, a feeling of nausea may be brought on by:

- Apprehension of the unknown

- Apprehension of the sensation of feeling nauseous

- Apprehension of making an error

What to Do About It?

First of all, do not worry about getting airsick. Even very experienced pilots can become nauseous in an unusual flight environment. Our instructors have been trained in alleviating factors that can contribute to motion sickness and will take action to help relieve any symptoms.

A positive, can-do attitude goes a long way toward ensuring your ability to obtain maximum training benefits during your training flights. Focusing on the objectives and procedures prior to and during each flight will help you prevent apprehension and motion sickness. Climb into the aircraft eager to tackle the fun-filled challenge ahead. With your understanding instructor behind you, just make the firm decision to overcome any perceived barriers and focus your mind on the task at hand.

The following is a list of things to consider before the flight to help prevent motion sickness:

- Ensure you are well rested and hydrated.

- Eat a light meal an hour or two before the flight.

- With a doctor’s permission, consider taking Dramamine about an hour prior to the flight if you have serious concerns related to nausea.

- With a doctor’s permission, consider obtaining a motion sickness “patch”.

The following is a list of things to consider airborne to prevent and alleviate motion sickness:

- Ensure your air vents are wide open and directed toward your face.

- Take slow, deep breaths.

- Keep your eyes outside the cockpit focusing on the horizon.

- Ask your instructor for a break.

- Ask to take control of the aircraft and just fly an easy, smooth flight path.

- Focus on the task at hand. Force your mind to think of something else besides your stomach.

- Ask questions. Make comments. Be pro-active in your training; do not allow yourself to become passive.

- If sickness becomes inevitable, do not be afraid to use the provided airsick bag. This is rare but it does happen on occasion. You will feel much better once you have released that menacing feeling.

Comments: