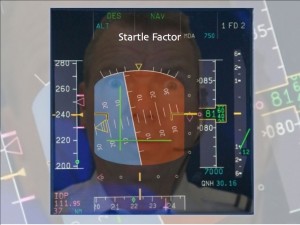

New guidance on Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) from the FAA and ICAO incorporate two terms to describe psychological factors that can be involved in unexpected airplane upset events. These terms describing the human factors impact from an upset are Surprise and Startle.

When we are learning to fly by reference to instruments, it is helpful to learn about aspects of physiology relative to aviation tasks. As an example, knowing how the vestibular system works can help us appreciate how a spiral dive can develop. In a similar manner, understanding a bit about neurophysiology, how the brain and nervous system work, can be helpful in understanding how our body reacts in an upset event. Being aware of how we are “wired” can help us determine what we can do to better prepare ourselves to react to unanticipated situations.

When we are learning to fly by reference to instruments, it is helpful to learn about aspects of physiology relative to aviation tasks. As an example, knowing how the vestibular system works can help us appreciate how a spiral dive can develop. In a similar manner, understanding a bit about neurophysiology, how the brain and nervous system work, can be helpful in understanding how our body reacts in an upset event. Being aware of how we are “wired” can help us determine what we can do to better prepare ourselves to react to unanticipated situations.

Let’s start by looking at how two different references define surprise and startle. The FAA advisory circular draft on UPRT says that surprise is “an unexpected event that violates a pilot’s expectations and can affect the mental processes used to respond to the event” while the ICAO Manual on UPRT defines surprise as “the emotionally-based recognition of a difference in what was expected and what is actual”.

For startle, the same FAA reference says it is “an uncontrollable, automatic muscle response, raised heart rate, blood pressure, etc., elicited by an event that violates a pilot’s expectations”, while the ICAO Manual says it is “the initial short-term, involuntary physiological and cognitive reactions to an unexpected event that commence the normal human stress response”. The FAA and ICAO categorize surprise as more along the lines of an emotional or mental response, with startle affecting us in a physiological or cognitive manner. Clearly these definitions indicate the blurry lines that exist when discussing these intertwined emotional/mental/physiological/cognitive responses.

It turns out that there is a physiological basis for these multi-faceted responses. We operate on two largely separate “circuits” depending on the level of stress we may be experiencing. When we are doing relaxed reasoning, like reading this post, we largely rely on the part of the brain that makes us uniquely human. It is the frontal lobe of our brain which allows for higher order reasoning, planning, and problem solving.

It turns out that there is a physiological basis for these multi-faceted responses. We operate on two largely separate “circuits” depending on the level of stress we may be experiencing. When we are doing relaxed reasoning, like reading this post, we largely rely on the part of the brain that makes us uniquely human. It is the frontal lobe of our brain which allows for higher order reasoning, planning, and problem solving.

However, certain threats don’t allow time for those time consuming niceties. When we are being faced with a physical threat to our safety, speed or strength may be more important than reasoning. For example, a lion doesn’t care how smart you are, you will taste just the same to him. To evade wild animals or other threats what is called for is muscular response, in this case involving running or maybe the ability to wield a rock or stick for defense. In these cases it is a primitive part of the brain called the amygdala that helps us out. The amygdala is involved in detecting and identifying cues or stimuli that could be threatening. The amygdala is spring-loaded to fire on two main things: novelty and uncertainty. It asks no questions and jumps into action making the heart beat faster and dilating blood vessels, sometimes even dumping in a bit of adrenalin or cortisol for good measure . What the amygdala will not do is make us smarter. In fact just the opposite can be true as the resulting excited state can make calm and rational decision making difficult.

The problem occurs when our body applies the response to a physical threat in a situation when the appropriate response requires more problem solving from our mind than from our muscle. In these cases, our body may have primed our “Fight or Flight” response when we are in a cockpit, where the threat may require wits instead of brawn and we have nowhere to run. This has been termed an “amygdala hijack” when the defensive response generated by the amygdala creates a combined emotional, physical, and cognitive response which is inappropriate for generating the correct recovery response.

This result of our innate threat response helps to explain another stress related effect often seen in the delivery of UPRT. This cognitive impedance is a reduction in the pace or speed of cognitive function. While startle and surprise are associated with the unexpected, cognitive impedance can result even from known, pre-briefed maneuvering that involves operating in unfamiliar attitudes which the amygdala will react to as threatening due the unusual and previously unexperienced nature of the stimuli.

This result of our innate threat response helps to explain another stress related effect often seen in the delivery of UPRT. This cognitive impedance is a reduction in the pace or speed of cognitive function. While startle and surprise are associated with the unexpected, cognitive impedance can result even from known, pre-briefed maneuvering that involves operating in unfamiliar attitudes which the amygdala will react to as threatening due the unusual and previously unexperienced nature of the stimuli.

While the amygdala serves an important role in self-preservation, it doesn’t contribute to overall intelligence. It is however very good at cataloguing events and stimuli that it has experienced before, and if those stimuli do not prove to be a threat, they can be removed from the threat list.

This is helps to explain the significant contribution that the experience of all-attitude flight can provide for pilots prior to encountering an unexpected upset event. Providing pilots with experience operating in the all-attitude domain, beyond attitudes normally encountered in everyday flight, provides habituation that reduces the cognitive disruption encountered when first experiencing these regions of the maneuvering envelope.

Resources:

– FAA advisory circular AC 120-UPRT, Upset Prevention

and Recovery Training

– ICAO Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery

Training

– Amygdala article by Dr. Simon Moss

Comments: