Recently I was in a meeting discussing aspects of our Aviation Performance Solutions (APS) training and a gentleman that I was speaking with stated that “Our pilots are CFI’s so they had to do spins, so there probably isn’t anything that you are doing that they haven’t seen.” There are a number of people that might think that and it is based on the belief that somehow the training requirements that are currently in place are precisely correct in what they provide for pilots in training. The assumption is that we are doing makes pilots as safe as possible so there isn’t really anything that we need to change.

No matter what side of the political aisle you prefer, there aren’t many people that view how the government works as “precisely correct”. A look at the accident record might suggest that there is at least some room for improvement in terms of the results that existing training delivers.

No matter what side of the political aisle you prefer, there aren’t many people that view how the government works as “precisely correct”. A look at the accident record might suggest that there is at least some room for improvement in terms of the results that existing training delivers.

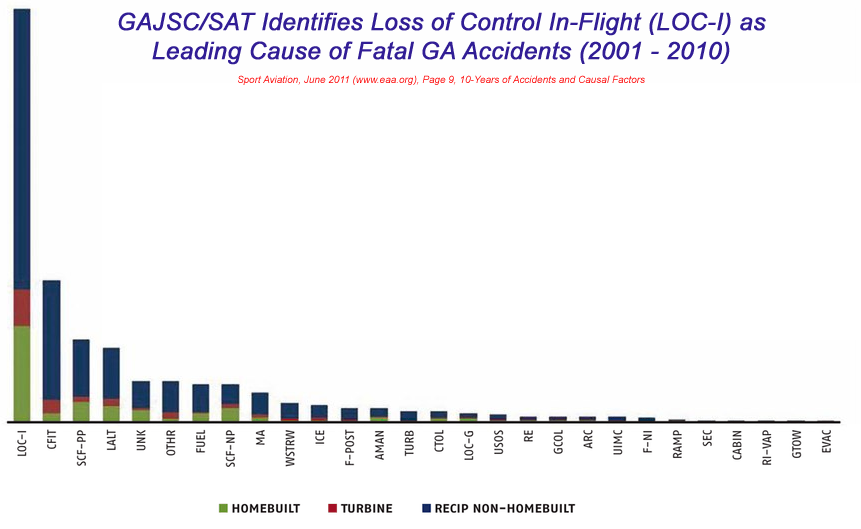

According to the U.S. General Aviation Joint Steering Committee, over a ten year period, Loss of Control In-flight (LOC-I) was responsible for significantly more fatalities than any other category. In fact, LOC-I had more fatalities than the next five categories combined. This would suggest that some changes in training to avoid LOC-I might be in order.

Unlike most flight training providers, APS does not begin with training regulations in mind. Instead, we chose to look at the accident record and ask the question, “What type of knowledge and skills could prevent these accidents from happening?” That is a fundamentally different question from “How do we comply with the regulations?”, and it has a fundamentally different result.

Most professional pilots today flying turboprop or jet aircraft are provided with training exclusively in full-flight simulators. Unfortunately, the limitations of full flight simulators may prevent the introduction to aircraft behavior and pilot skills that may be of great benefit in an unanticipated airplane upset event. Those limitations can prevent the presentation of knowledge and practice of skills that could be of the most benefit in keeping an airplane upset encounter from resulting in a LOC-I accident.

Most professional pilots today flying turboprop or jet aircraft are provided with training exclusively in full-flight simulators. Unfortunately, the limitations of full flight simulators may prevent the introduction to aircraft behavior and pilot skills that may be of great benefit in an unanticipated airplane upset event. Those limitations can prevent the presentation of knowledge and practice of skills that could be of the most benefit in keeping an airplane upset encounter from resulting in a LOC-I accident.

Simulators are limited in the amount of angle of attack and sideslip data that is required by certification. It can also be dangerous to take Transport category airplanes to the ranges of the flight envelope where they might go in an upset event. Because of this some of the dynamic aerodynamic behavior that occurs at combined high angles of attack and sideslip are not modeled and cannot be accurately replicated in the simulator environment. This means that pilots trained exclusively in a simulator will be denied experience with the lateral instability and sometimes violent roll-off characteristics that can be met with in such situations. This leaves them unprepared for the necessary recovery actions and is certainly a contributing factor to the accident rates that we see.

At APS, we are the largest provider of Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) in the world today. APS provides UPRT in a variety of Level D full flight simulators, fixed base flight training devices, and a fleet of Extra 300L and Slingsby T-67 aircraft. This makes us very familiar with the benefits and limitations of the full range of training resources available for instruction in the UPRT domain.

Airplanes don’t have an issue with limited data, as their behavior comes from the flow of air molecules rather than the flow of limited data. They are not virtual flying machines, but deal with the same set of aerodynamic principles facing all airplanes whether they are large or small; fast or slow. Although individual control forces, roll and pitch rates and other factors may differ, basic aerodynamic phenomena can be illustrated with an all-attitude/all-envelope capable aircraft when demonstrated by, and practiced with, an appropriately qualified instructor. Issues associated with exposure to physical forces due to acceleration and the psychology of the actual flight environment are also considerations that favor UPRT “in actual flight” as ICAO words it in their new Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training.

Issues associated with exposure to physical forces due to acceleration and the psychology of the actual flight environment are also considerations that favor UPRT “in actual flight” as ICAO words it in their new Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training.

As good as the record of aviation safety is, it can always be improved. It is unlikely to get much better, however, by continuing to do exactly what we are doing today.

Comments: