The 22% Solution: Alternate Control Strategies

In preparation for the article below, please review the APS Transfer of Skill Discussion.

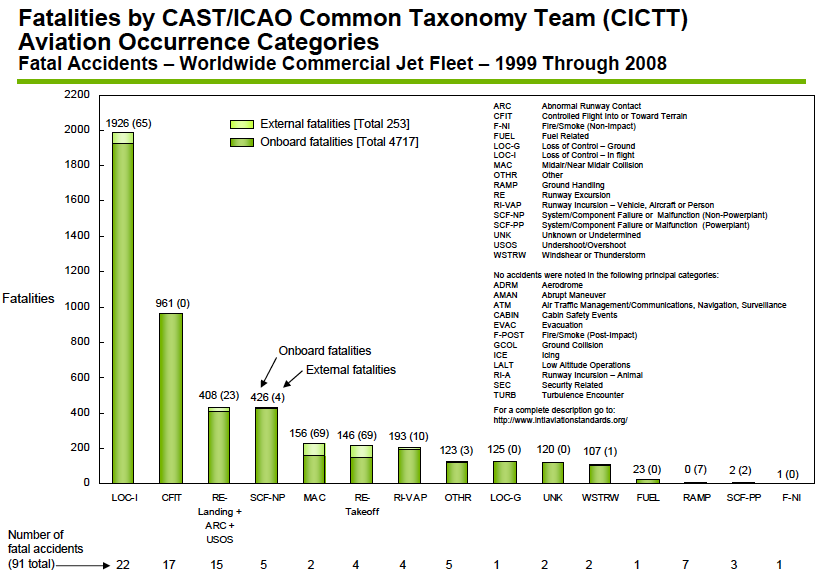

In Figure 1 below, it is well supported by analyzing the presented statistics that Primary Control Strategies must be the primary focus, however, Alternate Control Strategy (ACS) training cannot be dismissed. In fact, if a comprehensive solution is to be developed, statistically ACS should comprise approximately 20% of the effort.

Again, not sure where the 20% number comes from?

Please read the APS Transfer of Skill Discussion.

Figure 1: CAST Statistics (1999 through 2008) – Click for Larger Image

As we look into Alternate Control Strategies (ACS), we’ll find that they require the pilot to have a firm grounding in Primary Control Strategies (PCS) first and foremost. PCS remains the dominant line of defense in every pilot’s skill set. It is when a situation is diagnosed as requiring an alternate control strategy or, more likely, when the PCS is ineffective, that a pilot must understand each critical flight control has a back-up in most aircraft designs.

For example, in a nose-high unstalled unusual attitude situation in transport category aircraft, the primary control strategy to get the nose down is to use the elevator to lower the nose by pushing forward on the control column with the assistance of trim (if available). If the nose will not come down, or perhaps the condition was created by a runaway trim anomaly, then the pilot must understand there are back-up / alternate control inputs that will assist in getting the nose down. If, in this case, the aircraft had under-wing mounted engines, a reduction of thrust may reduce the associated nose-up rotational moment and allow the nose to come down. If there is still no success or overly slow response then utilizing aileron to roll off the lift vector could be the next valid step. If, due to the aircraft being in a high angle of attack condition, the ailerons were ineffective in rolling off the lift-vector, then judicial use of rudder using extreme caution may be required to accomplish the roll to allow the nose to be lowered to avoid the primary threat of a nose-high stall.

Each control has a back up in most situations. To effectively use a primary control in its alternate function, the pilot must thoroughly understand how the control is used in its primary role.

In the 22% of LOC-I scenarios that may require Alternate Control Strategies, the situation can vary from straightforward to complex. Advanced / complex alternate control strategy instruction is very challenging to develop a level of consistency and proficiency in pilots over the long-term. However, it does have significant value. The more complex the scenario, the more training the pilot requires to become competent at dealing with it. In addition, the relative performance of alternate control inputs to counter-act a failed primary control varies significantly between aircraft. Although a fundamental strategy and general know-how of ACS is crucial to a pilot’s skill set, these strategies must be implemented in a high-fidelity full-flight or programmable in-flight simulator that is a certified replica of the pilot’s specific aircraft.

Comments: