Summary

Stress is an inevitable part of flying and can have lasting adverse effects on tasks critical to safe flying such as attention, memory retrieval and problem solving. When chronic stress combines with acute stress caused by loss-of-control in-flight (LOC-I) or other emergency, a pilot’s ability to perform in that crisis can be degraded significantly. This article addresses how adrenalized learning in UPRT can enhance a pilot’s ability to cope with stress during a crisis. Exposing pilots to realistic task-relevant stressors while they develop proper skills and awareness to recover from training events will better enable them to react in a timely and efficient manner in the presence of similar stressors during a similar real-world event.

Author: Karl Schlimm, Director of Flight Operations, Aviation Performance Solutions LLC (APS)

Originally published in Skies Magazine

Overview Video

White Paper: Channelling Adrenaline in Upset Prevention and Recovery Training

Download: Skies Magazine Article – Channelling Adrenaline

Introduction

Stress is an inevitable part of flying. Chronic or long-term stress and time pressure can have lasting adverse effects on attention, memory retrieval and problem solving. When the detrimental effects of chronic stress combine with those of acute (short-lived event specific) stress caused by an aircraft emergency such as loss-of-control in-flight (LOC-I), the negative effect on pilot performance can be catastrophic. “Adrenalized learning,” a term coined by Rich Stowell (Master CFI – Aerobatic), is synonymous with stress-enhanced learning in a training environment. It can enable a pilot to effectively cope with acute stress during a crisis. The result of such training is a pilot who, when faced with an unexpected crisis, can avoid panic, engage in correct, timely response to sensory cues, and react quickly in a skilled manner to cope with the emergency. As a side benefit, proper training can instill long term confidence in a pilot to handle a crisis, therefore reducing chronic stress and its detrimental effects.

Stress is an inevitable part of flying. Chronic or long-term stress and time pressure can have lasting adverse effects on attention, memory retrieval and problem solving. When the detrimental effects of chronic stress combine with those of acute (short-lived event specific) stress caused by an aircraft emergency such as loss-of-control in-flight (LOC-I), the negative effect on pilot performance can be catastrophic. “Adrenalized learning,” a term coined by Rich Stowell (Master CFI – Aerobatic), is synonymous with stress-enhanced learning in a training environment. It can enable a pilot to effectively cope with acute stress during a crisis. The result of such training is a pilot who, when faced with an unexpected crisis, can avoid panic, engage in correct, timely response to sensory cues, and react quickly in a skilled manner to cope with the emergency. As a side benefit, proper training can instill long term confidence in a pilot to handle a crisis, therefore reducing chronic stress and its detrimental effects.

Negative Effects of Stress

Stress produces both psychological and physiological (or “psychophysiological”) effects on an individual which can be advantageous or detrimental in a crisis. We actually encounter some stress anytime we perform a task. A stress response results in elevated physiological arousal, often associated with the release of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline.

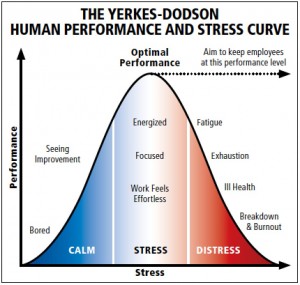

The relationship between these hormone levels and associated performance enhancement is in the shape of an “inverted U” curve, meaning elevated levels of these stress-induced hormones enhance performance up to a certain level, before becoming detrimental. Our vision and hearing become more acute as stress levels increase enabling us to perform better. The physiological arousal in response to stressors is designed to help the body adapt quickly to survive and eliminate the stressful stimuli. This is our instinctive “fight or flight” response. Stress,simply put. not only enables but enhances performance, up to a certain level. It is critical that acute stress in an emergency or loss-of-control-inflight event not become so elevated that it leads to panic or otherwise incapacitates the pilot. Much has been written and studied on the negative effects of stress, both acute and chronic, on learning and performance of a task. Acute stress during a crisis combined with a pilot’s sense that he has no control over the situation can lead to panic, inaction or errors which could be fatal. The chronic stress omnipresent in a pilot who flies constantly in fear of encountering a situation he or she cannot control can have lasting detrimental effects on the body as well as memory. Cumulative excess stress can adversely impact our working memory and ability to process information especially when exacerbated by the acute stress generated in a crisis.

The relationship between these hormone levels and associated performance enhancement is in the shape of an “inverted U” curve, meaning elevated levels of these stress-induced hormones enhance performance up to a certain level, before becoming detrimental. Our vision and hearing become more acute as stress levels increase enabling us to perform better. The physiological arousal in response to stressors is designed to help the body adapt quickly to survive and eliminate the stressful stimuli. This is our instinctive “fight or flight” response. Stress,simply put. not only enables but enhances performance, up to a certain level. It is critical that acute stress in an emergency or loss-of-control-inflight event not become so elevated that it leads to panic or otherwise incapacitates the pilot. Much has been written and studied on the negative effects of stress, both acute and chronic, on learning and performance of a task. Acute stress during a crisis combined with a pilot’s sense that he has no control over the situation can lead to panic, inaction or errors which could be fatal. The chronic stress omnipresent in a pilot who flies constantly in fear of encountering a situation he or she cannot control can have lasting detrimental effects on the body as well as memory. Cumulative excess stress can adversely impact our working memory and ability to process information especially when exacerbated by the acute stress generated in a crisis.

Types of Stress

Most of this discussion centers on acute stress, although chronic stress from time pressure, general apprehension in a flying environment or from non-flying related life events may lower a pilot’s threshold of tolerance for acute stress (the ability of proper training to lower chronic stress specifically cannot be discounted). Acute stress can be either intrinsic (related to the specific event or crisis) or extrinsic (external to the event). The intrinsic stress of a wake turbulence encounter, for instance, involves startle, visual cueing of seeing the ground fill the windscreen, realization of being upside down and close to the ground, self-doubt as to successful outcome of the event, and somatosensory cues such as increase in acceleration forces in different directions, etc. Extrinsic stress may arise from stressors present at the time of, or just before the wake turbulence encounter, that would be present regardless of whether the wake turbulence encounter occurred. These stressors include elements of the task-intensive time-compressed approach and landing environment, and even subtle stressors such as heat and vibration. Ground proximity is both intrinsic and extrinsic in that it was a stressor before the wake turbulence encounter – its criticality being enhanced significantly by being overbanked. Acute intrinsic stress represents our instinctive “fight or flight” response to a potentially life threatening event (while “fight or flight” is indeed instinctive, recovery from a wake turbulence encounter or other LOC-I event is not instinctive, but rather learned).

Individual Reaction to Stress Varies Widely

To be clear, it is not the event itself that guarantees a fixed level of stress, but rather a person’s reaction to the crisis that determines his/her level of stress. According to Kim and Diamond “The Stressed Hippocampus, Synaptic Plasticity and Lost Memories,” the most significant factor in determining the level of stress response to a crisis situation is the individual’s perceived level of control over the situation. For instance, a pilot who has been upside down in an airplane before (ideally first in a training environment), who has the skills to recover from that event with minimal altitude loss and who understands that any aircraft can be rolled upright, will have a relatively low detrimental stress response to such an unplanned occurrence. Conversely, a pilot who has never been upside down, has never developed motor skills in an aircraft to recover from such an event and who fears the possibility or eventuality of being upside down in an aircraft, may be incapacitated by the cumulative stress incurred in that event.

Interestingly, even without proper training, some pilots will always feel more confident and in control of certain situations than others. Pilots who regularly deal successfully with high levels of stress or fly in aggressive flight regimes (such as some military pilots) generally have higher confidence even in flight environments in which they are not that familiar. Again this confidence does not always mean that they will act correctly and efficiently in a crisis. Conversely, other pilots carry an ingrained fear of losing control. The reasons for this vary, but their fear could have originated from a previously experienced startling event such as a wake turbulence encounter, or an unplanned spin from which that pilot felt helpless and lucky to recover. It could also have originated from a negative and perhaps traumatic training experience. Such an undesirable experience could be generated when when an instructor does not build up properly to a training event, does not manage stress properly in the training environment, or creates a situation too far beyond the ability of the student. An example of this would be putting a student into a spin and telling him to recover without adequate academics and inflight demonstration. The instructor has, in effect, introduced a startling event before the student has developed the proper skills and confidence to handle such an event.

Experience is not a guarantee that a pilot will feel more in control of a situation. The adage, “there are old pilots and bold pilots, but no old bold pilots” may ring true in certain cases. For instance, a 25,000 hour career corporate pilot who has spent a lifetime avoiding bank angles over 30-45 degrees even in the training environment may eventually and inadvertently develop such an inherent fear of being upset in flight that the probability of that pilot panicking in that upset event is very high. Conversely, a young low-time pilot who arguably does not “know enough to be afraid” of an overbanked situation, and who has effectively, albeit somewhat subconsciously, managed his acute stress to a reasonable level, has a higher probability of avoiding panic in the same crisis. Again, proper skill development in a training environment is critical. But the instructor’s role in management of stress in the “adrenalized learning” environment becomes easier with the “fearless young student.” His/her task will be more difficult with the timid or apprehensive student, but the instructor must accept this challenge.

The Advantage of “Adrenalized Learning”

The concept

The concept

of Adrenalized Learning involves properly conducted stress-augmented training to increase skill level, retention and follow-on performance in real-world stressful encounters. Why is it important to expose pilots to acute stress in the training environment? We’ll look at this topic specifically within the context of UPRT (Upset Prevention and Recovery Training). The objective of any UPRT training task must be to prepare a pilot to successfully handle that task in the “real world.” The question therefore becomes, what task elements are critical to the successful outcome of a loss-of-control inflight event? Put simply, these are the critical tasks:

1) Maintenance of a high level of Situational Awareness (SA) to include threat planning (e.g. a pilot recognizes the potentially fatal threat of wake turbulence while preparing for and on final approach, and is on guard)

2) Proper Interpretation of visual cues (backed up by other sensory cues) in an escalating or upset event, often requiring previous exposure in the training environment

3) Correct and timely response to cueing, necessitating proper skill development

4) Proper Stress Management

High levels of stress can have a significant impact on a pilot’s ability to perform all of the other necessary functions from maintaining SA, interpreting cues correctly and performing task-essential activity. Specifically, extreme levels of stress can cause the following:

1) Narrowing of visual field and fixation

2) Reduction of situational awareness in general

3) Reduction in effectiveness of information processing

4) Poor judgment

5) Inhibited working memory and memory recall

6) Increase in reaction time

7) Negative impact on accuracy and motor function

8) Non-task activity (pilots perform tasks not relevant to the priority activity such as a safe recovery, e.g. raising flaps during stall recovery, or pulling through in a nose low overbanked upset)

9) Over-reaction

10) Cognitive bias (which may cause a pilot to feel more aware and informed that he really is, thus making decisions on incomplete or inaccurate data)

Can stress-based or “adrenalized” learning be effective?

Clearly, appropriate cognitive functioning during stressful events is important in aviation. Since our ability to think and react clearly and correctly in a crisis can be so adversely impacted by excess levels of stress, an important question to ask is, can a properly structured training environment enable a pilot to react to a given crisis with manageable, non-incapacitating, performance-enhancing levels of stress? This question is important because elevated stress levels in certain real-world events are inevitable despite training. For instance, a wake turbulence encounter close to the ground with its associated startle factor will inevitably produce elevated levels of stress in most pilots despite training in such a crisis. Although properly conducted training can allow a pilot to keep stress to non-incapacitating levels, it will always be there. Therefore, despite the fact that pilots trained properly will learn to react to a crisis with reduced stress, they must still be trained to react correctly in the face of startle factor and elevated stress.

How can the training environment be structured to use “adrenalized learning” to better prepare pilots for a crisis?

Logically, the more realistic the training is to a real-world encounter, the more effective it will be. Thus, if the type of stress is realistic and relevant to the task, it will have a more beneficial effect on training. There are, however, other considerations. Again we’ll look at Upset Prevention and Recovery Training. For the typical pilot untrained in upset recovery, exposure to more extremes of bank and pitch will produce a commensurate higher level of stress. Exposing a pilot-in-training to too high a level of stress too soon can produce a negative training experience and actually have a negative effect on the pilot’s ability to cope with stress. If a pilot’s confidence is shaken in the training environment, that pilot could carry with him elevated levels of chronic stress when flying even in a routine environment. This can have long-term debilitating physical and mental effects and reduce the pilot’s threshold of incapacitating stress in a crisis. Properly structured and conducted reality-based training is critical and the instructor plays a key role in real-time management of this training based on a student’s individual needs. Following are some elements of a properly structured “adrenaline-based” training environment:

Positive Learning Environment

A positive learning environment should be established and managed. Ideally the instructor should determine through proper questioning if the student has ever had a traumatic real-world or training experience. The instructor should then tailor part of the training to increase the student’s confidence in the successful outcome of that specific traumatic event.

Safety Margins

It is critical in an on-aircraft training environment that the the student have absolute and justified confidence in his instructor’s abilities, in the margin-of-safety of the training aircraft and in the margin of safety of the flight environment. The instructor must ensure that safety-of-flight is never compromised. Realistic stressors can be incorporated within these constraints. For instance, a skidded turn stall or simulated wake turbulence encounter can be conducted in closer proximity to the ground than a nose low overbanked upset from a simulated cruise altitude. In any case, the instructor must ensure adequate ground clearance at or exceeding mandated minimums, as well as recovery within the structural (to include airspeed) limits of the airplane given worst-case training scenario.

Building Block Approach

Incorporate the “Building Block Approach” into training. This includes gradually exposing the student to increasing nose-up, nose-down and overbanked attitudes and also increased deviations both high and low airspeed so that he can increase his ability to manage stress in those situations. Exposing the student to extremes of pitch and bank or airspeed too early or abruptly can have lasting detrimental effects on a pilot’s confidence and ability to manage stress. Exposure to more extremes of attitudes must be progressive.

Context Relevant Stress

“Context relevant stress” should be incorporated into training. The instructor should look for opportunities to ensure that stressors (stimuli that induce stress) be as realistic as possible and relevant to the training task performed. For instance, since a worst-case Graveyard Spiral typically involves a nose low high bank angle attitude with high speed and high G-loading, the instructor should ensure that the student is coached into a spiral dive in the training environment with similar cues – suitable nose attitude and bank and enough speed and G-loading to create the associated wind rush, pitch loading due to trim, control sensitivity associated with high speed flight, and sense of urgency due to ground proximity. The student must then recover in the presence of these realistic stressors. Since similar stressors will be present in a real-world spiral, the pilot will be able to think and act more clearly in the presence of those stressors because he’s already seen them in the training environment in a task-relevant environment. Another example of context relevant stress is the setup of a realistic wake turbulence encounter. The instructor could state…”for this next scenario, I am the pilot flying, you are the pilot monitoring, we are in your Learjet at 1200 feet on final approach and configured at Vref.” The instructor then configures the aircraft at a representative approach speed with associated control sluggishness, performs the simulated wake turbulence maneuver and directs the student to recover.

Visualization

Context relevant stress can be enhanced through “facilitated visualization.” Realism can be added if the instructor can effectively encourage the student to visualize performing the task in his own aircraft. For instance, the instructor could state before performing a Split-S type maneuver to show the incorrect response to a nose low overbanked upset… “I will demonstrate a Split-S maneuver now, but I want you to picture yourself inadvertently pulling through an overbanked nose low upset in your Gulfstream aircraft and imagine the altitude lost and airspeed gained in that aircraft.” In fact the emphasis of transfer of skill is a critical part of upset recovery and prevention training.

Confidence and Skills before Startle

Instill confidence in the student by successfully building up core skills, the ability to gain and maintain enhanced awareness and timely decision making. Once the student has gained these basic skills and confidence, the instructor can introduce the “Startle Factor” at the appropriate point in training. The “startle” reflex is somewhat involuntary. When there are extreme differences between expectation and reality with rapid onset, such as a wake turbulence encounter, the body initiates the “fight or flight response.” Because the occurrence of these events is a very real possibility, pilots should be taught to react correctly and in a timely manner despite the extreme stress associated with such an event. This stress can be controlled in the training environment.

Exposure to Wide Range of Stressors

Expose the student to a wide range of task relevant stressors. For instance, nose low overbanked upsets can happen at both low airspeed (close to stall) or high airspeed and at low or high altitude. The instructor could expose the student to nose low overbanked upsets first via a skidded turn stall. This is typically a low altitude low airspeed upset directly attributable to pilot error (with the commensurate emphasis on why it is so important to avoid it in the first place). This task should be set up with suitable but safe ground proximity and at a representative approach speed. Then the instructor could expose the student to increasingly greater overbanked and higher speed upsets with associated sensory cues – sound of wind rush, increased G on recovery, etc. While a skidding turn stall and its associated overbanked attitude is very beneficial in skill development as well as the emphasis on avoidance, stressors are different in that task than in a high speed overbanked upset. Low speed stressors would be closer proximity to the ground, control sluggishness and associated slow control response, etc. Not exposing the student to both types of upsets would be doing the student a disservice.

Management of Stress

Manage stress throughout the flight profile. Sustained stress should be avoided. Training should be a balance between sympathetic neural activities (i.e. those preparing the body for action, like elevated heart rate), and parasympathetic neural activities (i.e. those functions that prepare the body for tranquility or relaxation). Training should incorporate adrenalized learning during tasks and relaxation between training events, especially while critique and instruction are given. Sustained stress will effectively “burn the student out” early and may have lasting detrimental effects particularly if confidence is not bolstered. All students are different and react to stress differently. The instructor must know when to take a step back. The training environment can never reach a level of extreme uncertainty, where the student is constantly apprehensive, never knowing what will happen next. This will negate the effectiveness of training and severely reduce the credibility of the instructor.

Advantages of On-Aircraft Training for Stressor Realism

While simulator based training has definite merit, a significant portion of training must be conducted in an actual aircraft which is appropriately certified for the task. Simulators generally lack perceived realism. The ground for instance is not a real threat. In an aircraft, even at a safe altitude, the ground is a real threat. In an aircraft, g-forces can be experienced. Auditory cues like wind rush are present. A sense of realism and urgency are present at a level typically not experienced in the simulator. Of course, if the simulator is representative of the aircraft that the student flies, certain stressors like internal systems warnings can be introduced that don’t exist in an aerobatic aircraft. In this sense, the simulator is an excellent tool with which to cap off UPRT training after aircraft training. Within the context of adrenalized learning, the student can be exposed to a wider diversity of stressors in this fashion.

Conclusion

Adrenalized Learning is a valid and valuable training tool. Realistic stressors that are task relevant and stress at realistic levels introduced at the right time can enhance the value and realism of training. Not only will the student learn to react in a correct and timely fashion in a real-world upset in the presence of acute stressors that he has already been exposed to in the training environment, but he will typically fly with decreased chronic stress or anxiety, e.g. chronic fear of the unknown (situations that he has not been exposed to in training). The overall objective of “adrenalized learning” is to reduce the adverse physiological response to external stressors while improving performance. A properly structured training environment should incorporate realistic stressors while exposing the student to a diverse range of training events. Emphasizing proper skill development and awareness despite presence of stress will facilitate the gradually increased level of confidence on the part of the student in the successful outcome of a real-world crisis. Any training that reduces fear of the unknown and increases awareness and confidence is valuable. UPRT training and any aerobatic or all-attitude training can be extremely beneficial in preparing a pilot to react in a correct and timely manner in an upset.

Comments: